In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with Tycjan Knut.

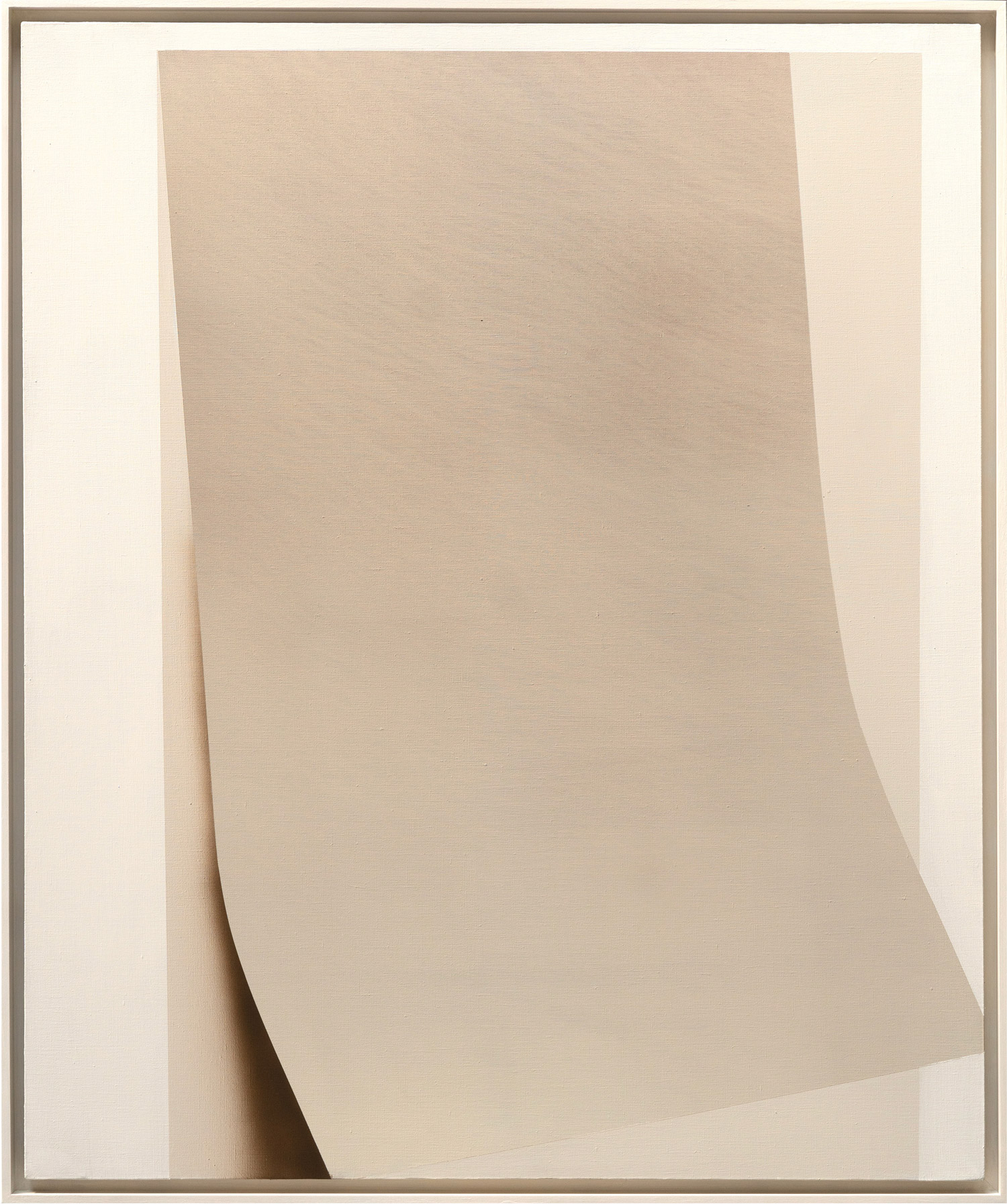

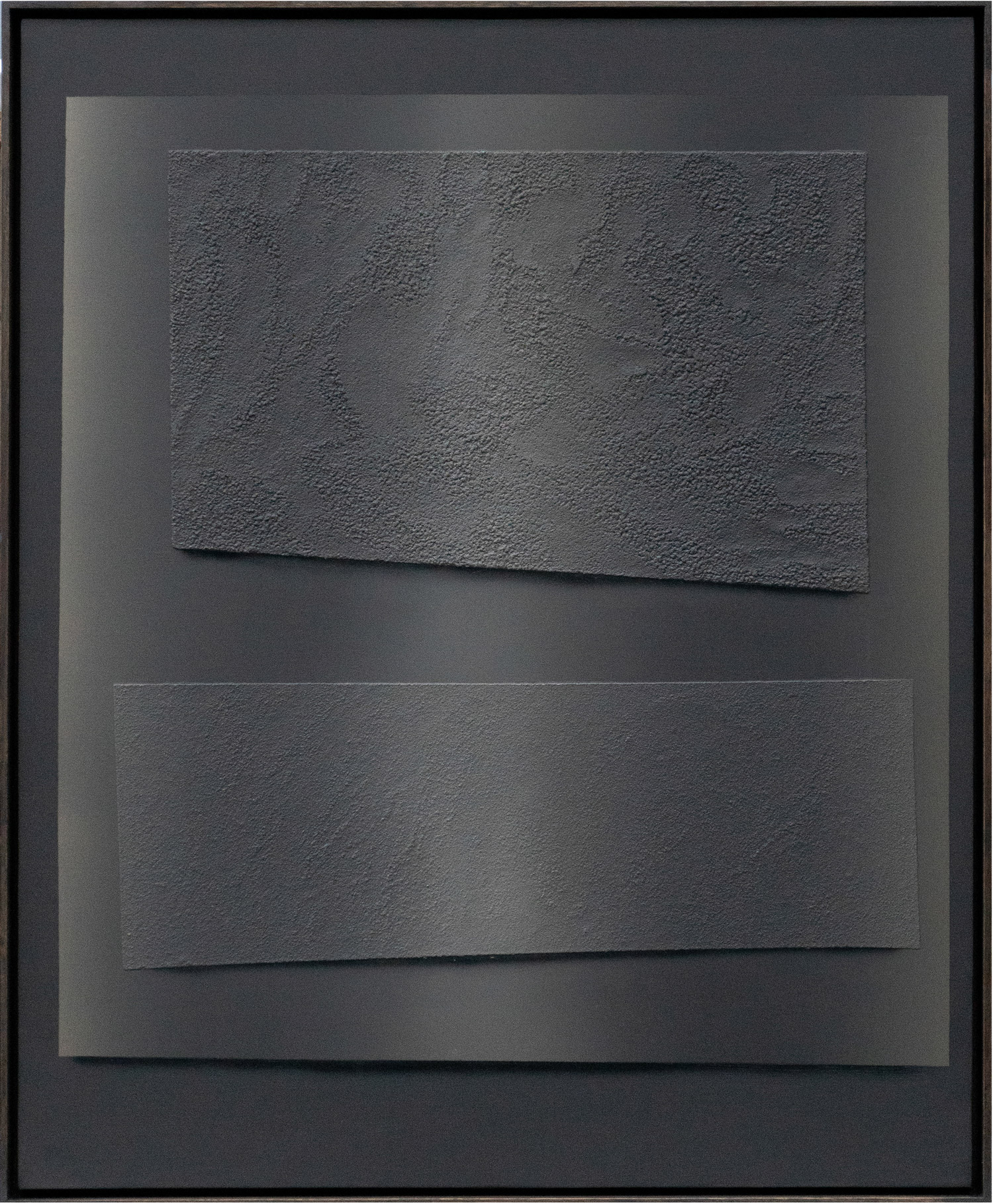

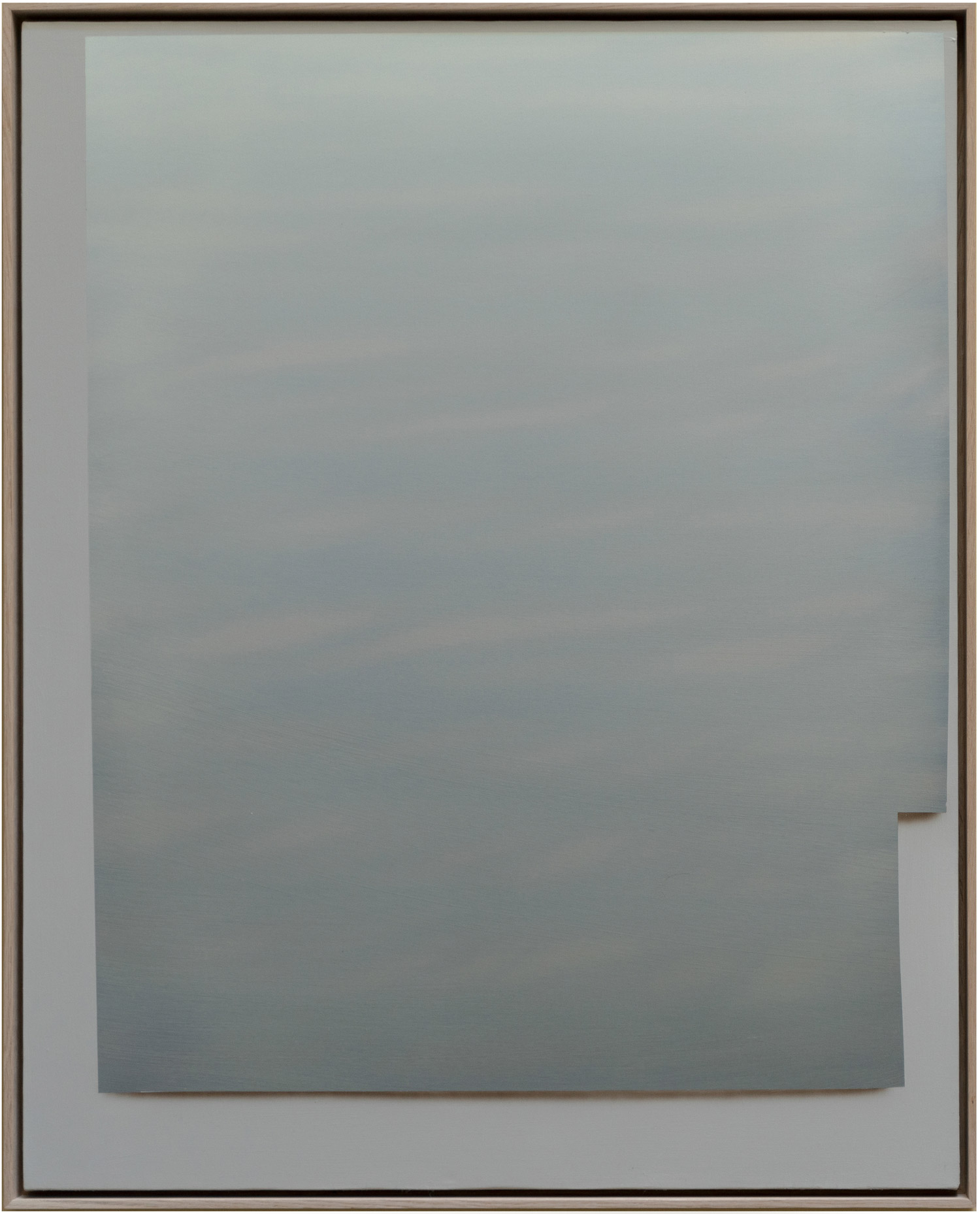

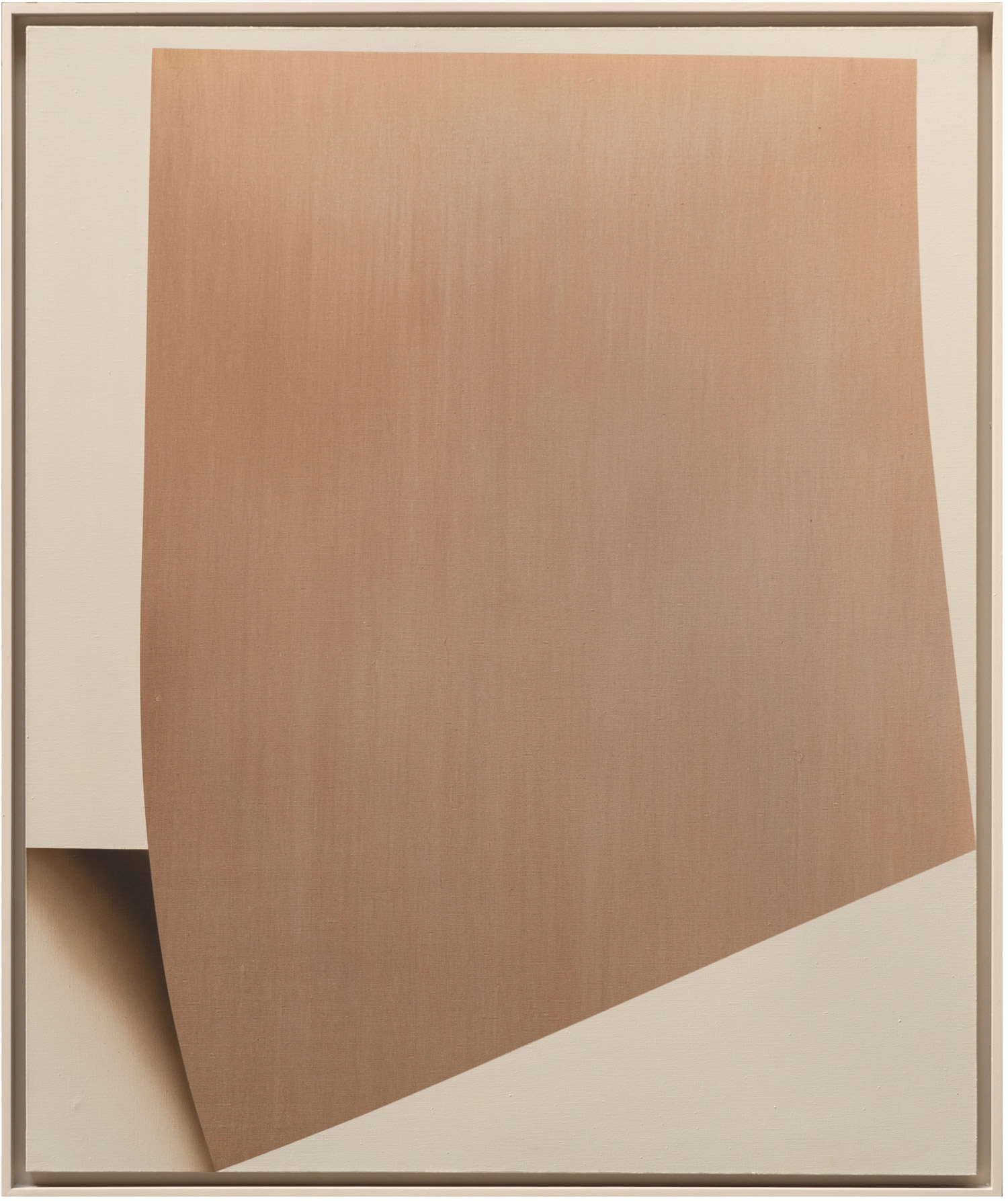

Tycjan Knut (b. 1985) is a Polish artist whose abstract compositions are characterized by their subtle balance of light, texture and color. His works emerge through an intuitive, reactive process without a plan or sketch, balancing raw spontaneity with refined precision.

In this interview, I spoke to Knut about his artistic roots – from his traditional training to the development of his unique abstract language. We also delve into the influence of Polish abstract artists of the 1960s and 70s, as well as his own creative process – a field of tension between discipline, experimentation and the courage to explore the unknown.

Tycjan, it’s great to be able to talk to you about your work today. You have a considerable formal education behind you – among other things, you completed your doctorate at the Jan Kochanowski University Institute of Fine Arts in Kielce. How has this time shaped your work today?

The PhD marked the end of a very long educational path. I began studying art when I was just six years old in my father’s small drawing and painting school. By the time I was in high school, I was already teaching classical drawing and painting there, which gave me a deeper understanding of technique and discipline from an early age.

I then attended the National Art High School, which was, in many ways, the most demanding stage. The workload and hours were intense—we studied the full spectrum: drawing, painting, calligraphy, design, sculpture, ceramics, and more. It was a very traditional and rigorous education, shaped in the old-school academic model with many hours of hands-on work.

After that, I went on to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, in the painting department. During my time there, I also specialised in sculpture and photography. It was around my third or fourth year at the Academy that I started shifting toward abstraction. Until then, my practice was rooted in classical approaches—still lifes, portraits, and landscapes.

The PhD came after, and it was an important moment—it fully solidified my direction as an abstract painter. I completed the doctorate with the highest possible marks and received all available scholarships, including an award from the Ministry of Culture. That financial and institutional support allowed me to dedicate myself fully to developing my work and pushing my ideas further.

I truly enjoyed the education process, but when I finally received my PhD at the age of 28, it was a huge relief—it had been such a long and intense journey, and it felt good to close that chapter.

You balance light, texture and color in your minimalist compositions. What questions drive you in your work? Are there formal problems that you find yourself returning to again and again?

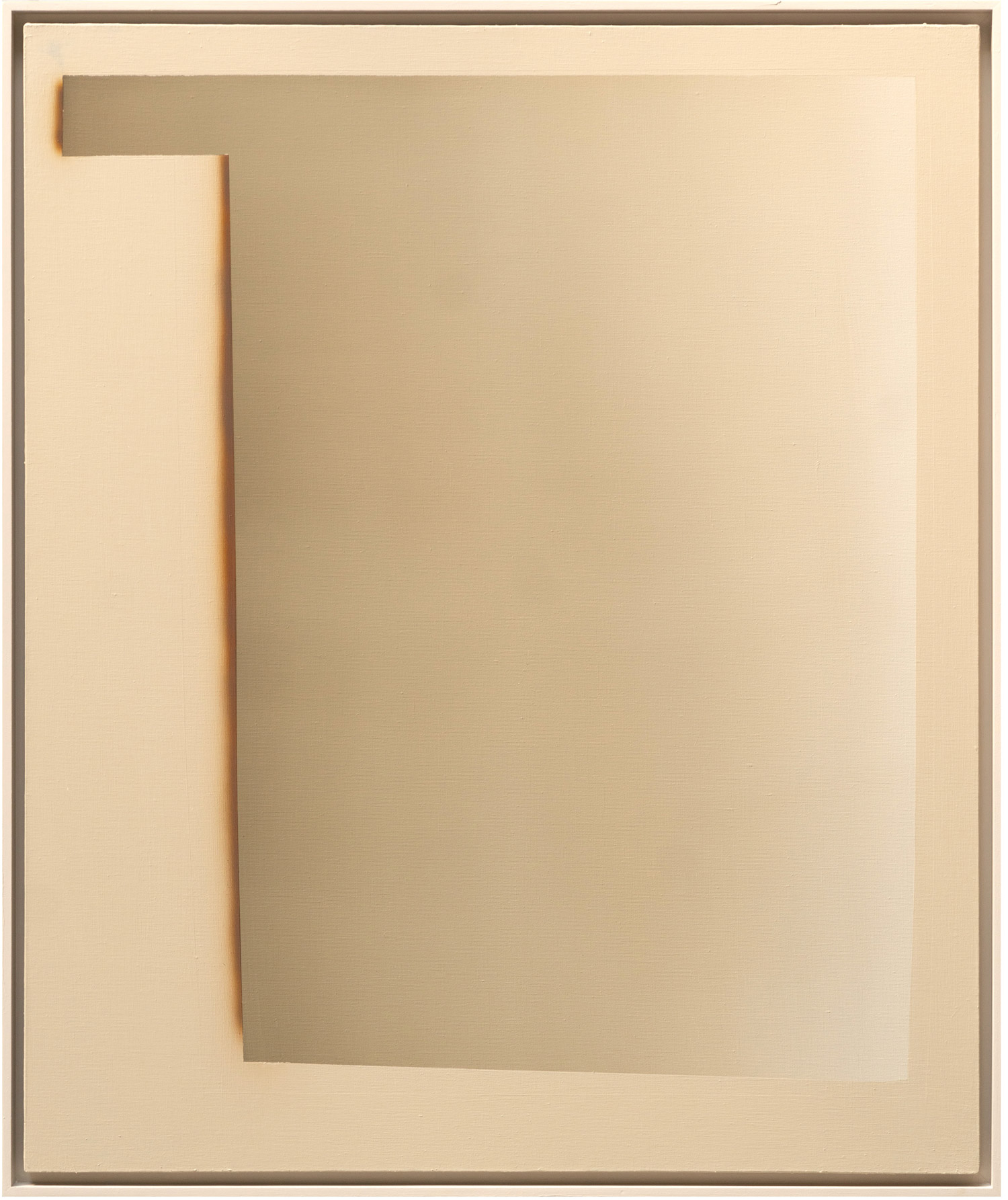

I work with gradients and the textures of free-flowing, layered paint. That’s the beginning of each painting—an intuitive, improvised phase where I let the material behave almost on its own. It’s raw, physical, and uncontrolled. But then, at a certain point, I impose structure. I begin to constrain that chaos into composition, turning a field of gradient or texture into a figure—something that holds presence.

This process is how I’m building my own visual language. I work in large volumes—it’s obsessive. For every work that achieves a new quality, there are hundreds of failed ones behind it. Each of those attempts is a moment where I try to introduce a new element or push the vocabulary forward. It’s incredibly challenging, but I’ve become addicted to that creative tension—the friction between intuition and control, failure and discovery. That’s where the real energy of the work lives for me.

Many artists find it difficult to use the term “minimalist” in relation to their work. How about you? Would you describe your works as minimalist?

It’s interesting—because the results of my work seem minimalistic, but I wouldn’t describe my practice that way at all. The visual outcome might be calm, meditative, even sparse—but what’s behind it is something completely different. I work with high intensity, often painting over 12 hours a day. For years, I lived in my studio. I produce a large volume of work, constantly shifting ideas, testing compositions, chasing something just out of reach. My process is obsessive, physical, and mentally demanding.

So while the viewer has every right to experience the paintings as minimalist, for me, the reality is much more dynamic. I’m constantly changing direction, pushing into new territory.

That said, in my personal life I am a radical minimalist—I live with only a cabin-sized suitcase of belongings, and I’m not interested in material things at all. So perhaps there’s a deeper alignment there, but in the studio, minimalism isn’t a guiding principle—it’s more like a mirage that emerges after.

You attach great importance to the choice of materials in your work. What inspires you in your choice of pigments and materials, and how do they influence the emotional depth of your works?

I mostly work with natural pigments—earth tones, oxides—because they carry an innate sense of harmony. There’s something timeless and grounding about them. I try to saturate these pigments through multiple layers of thin paint, slowly building depth without relying on surface shine. These materials don’t reflect too much light, which is important to me—my eyes rest in that kind of environment. It’s one of the reasons I’m so drawn to Italy, especially Florence—the palette of the architecture and landscape there feels completely aligned with my sensibility.

That said, I do make exceptions—for instance, in my blue paintings, where I deliberately step outside that natural palette. But even then, it’s about emotional resonance, not just color.

Right now, I’m in Colombia, exploring the possibilities of using local natural pigments. The colors here are incredibly saturated and vibrant—there’s a whole new kind of energy in the materials. I’m very curious how that might influence the atmosphere of my work moving forward.

The results of my work seem minimalistic, but I wouldn’t describe my practice that way at all. The visual outcome might be calm, meditative, even sparse—but what’s behind it is something completely different.

You work without sketches or plans and describe your approach as reactive and intuitive. How do you begin the dialogue with the canvas and are there moments in your process that you find particularly challenging?

I work without sketches or fixed plans—everything begins directly on the canvas. My approach is reactive and intuitive. I usually work on 20 to 30 paintings at the same time. In the beginning, I might simply cover some of them in a single color, create a gradient, or just spill paint. These first gestures are fast and instinctive—like opening a dialogue with the material.

Having that many canvases in progress gives me space to move freely. There’s no pressure to resolve anything immediately, and because there’s always something happening, there’s never any idle time. I can shift from one painting to another depending on what feels right in the moment. That flexibility is essential—it keeps the energy flowing and prevents overthinking.

The most challenging part comes later, when the intuitive chaos has to be shaped into a coherent composition. That tension—between spontaneity and control—is where the work really happens. Some paintings come together quickly, but others fight back. I might live with a painting for weeks, unsure how to resolve it. Knowing when to stop, when to hold back—that’s the hardest part. But it’s also what keeps me coming back.

You enjoy delving into archives to rediscover lost abstract Polish artists from the 1960s and 70s. What fascinates you about this era and what significance do you think this heritage has for the contemporary art world?

Yes, I’ve spent a lot of time looking into the archives, especially rediscovering abstract Polish artists from the 1960s and 70s. There’s something incredibly raw and authentic about their work—many of these artists were operating under difficult political and material conditions, yet they managed to create visual languages that felt completely free, deeply formal, and often ahead of their time.

What fascinates me most is their sense of dedication and restraint. They worked with limited resources, but with an incredible clarity of vision. Their approach to abstraction wasn’t decorative—it was conceptual, physical, often philosophical. I think that legacy is very important today, especially in a moment when abstraction is being revisited globally but often without deep roots or historical context.

For me, this heritage is not just about national pride—it’s about continuing an interrupted conversation. Many of these artists were under-recognized or forgotten, partly due to political isolation. But their work holds immense value, and I feel a responsibility to keep that dialogue alive—both by acknowledging their influence and by pushing the language of abstraction forward in my own way.

That tension—between spontaneity and control—is where the work really happens.

How do you define “beauty” in art for yourself? Has your understanding of aesthetics changed over time?

For me, beauty isn’t something I can define intellectually—it’s purely physical. When I see something truly beautiful, I feel it in my body. My hair rises on the back of my head, I get goosebumps—it’s an involuntary reaction. That’s how I know a painting is powerful, whether it’s mine or someone else’s.

It’s not about theory, composition, or meaning—it’s about presence. Something hits you, completely bypassing analysis, and stays with you. That physical response has been my guide for years. It’s the only real measure I trust.

And finally: What are you working on right now, and what are your plans for the future? I read that you are currently revisiting figurative elements again to find new solutions within abstraction.

It’s a very long and private process. I’ve been secretly working on figurative pieces—drawing plants, painting landscapes—but I’ve never shown them to anyone, not even friends. I’m not sure where it’s going yet. Being in Colombia has had a big impact on this shift. The forests here are overwhelming—so much diversity in a single frame, such richness of texture, and endless shades of green. Green was a color I avoided for years, but now I find myself completely immersed in it.

I don’t know if I’ll ever show these figurative works publicly, but I’m certain they’ll influence my abstract work. They’re opening something up in me. I think that’s what keeps the practice alive—not knowing exactly where it’s going, staying open, taking risks in silence. That uncertainty is important. It keeps me grounded and curious.