In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with Søren Sejr.

Søren Sejr (b. 1981) is a Danish artist whose abstract works explore the interplay of texture and light. From monochrome black surfaces to his recent vivid color compositions, Sejr’s work is guided by curiosity and constant renewal. Through his minimalist yet tactile approach, Sejr investigates how the surface can become something that resonates beyond its physical boundaries.

In this interview, I speak with Søren about his artistic beginnings and the evolution of his visual language. He shares insight into his creative process, the joys and challenges of working with both color and monochrome black, how imperfections and patience continue to drive his work forward, and what led him back to color after years immersed in black.

Søren, thank you for your time! Please tell us how your artistic journey began. Was there a defining moment that led you to become an artist?

My path into art started without any grand plan. As a teenager in Lemvig, I spent my time playing football and hanging out with friends. A local artist who painted chickens with tiny dots fascinated me. I cut up an old sheet and tried to paint my own hens – they were terrible, but I realised it was possible to conjure an image out of nothing. My mother then enrolled me in an evening art class. Those Thursday evenings felt like stepping into another world; three hours flew by like twenty minutes. I was hooked on the feeling of being pulled into a different dimension, and that sense of immersion still drives me today.

How would you describe the development of your artistic work over the last few years? You have worked with various mediums and styles – from monochrome black paintings to reliefs made from burned wood and geometric color fields. Despite all these different styles, however, you have consistently remained true to an abstract and reduced visual language. What guides you in all these explorations?

Curiosity guides everything I do. When you look back at my work, it might seem like I jump from colorful stripes to monochrome black surfaces, from burnt wood reliefs to geometric color fields, but there’s always a common thread. During my studies at the Aarhus Art Academy (2006–2010), I worked with geometric compositions in yellow, green, blue, brown, and white.

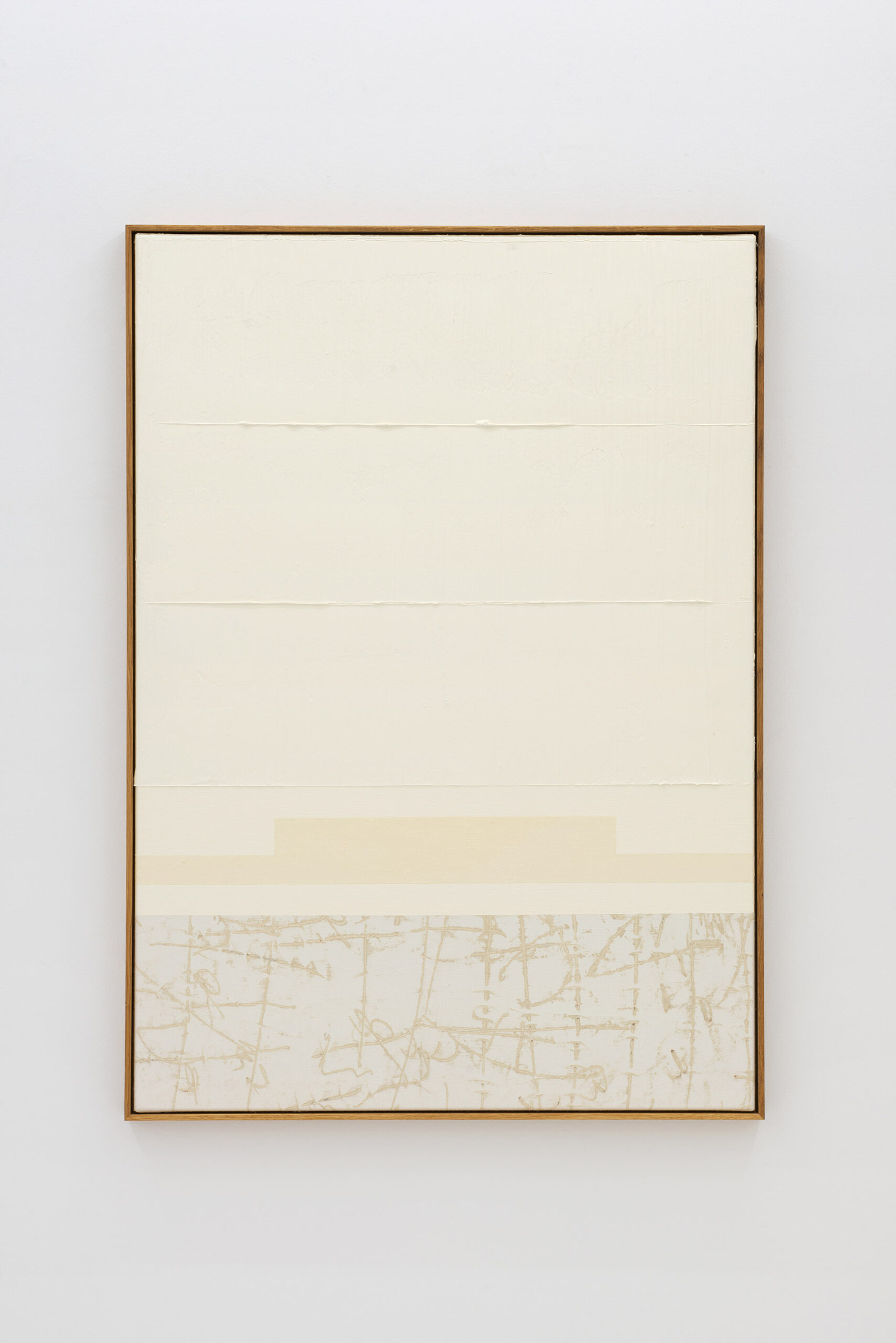

Around 2017 my practice shifted toward minimalism; large monochrome, mostly black surfaces became typical, and I disrupted them with spontaneous, abstract lines. At the same time, I began assembling recycled wood into reliefs and burning them with the Japanese Shou Sugi Ban technique, creating cracked, matte black surfaces that change with the light. Each series contains the seed of the next; an imprint or material that intrigues me becomes the starting point for further exploration. I’m not interested in repeating myself or copying others – missteps and detours are how my own language has emerged.

How would you describe your art to someone who has never seen it before?

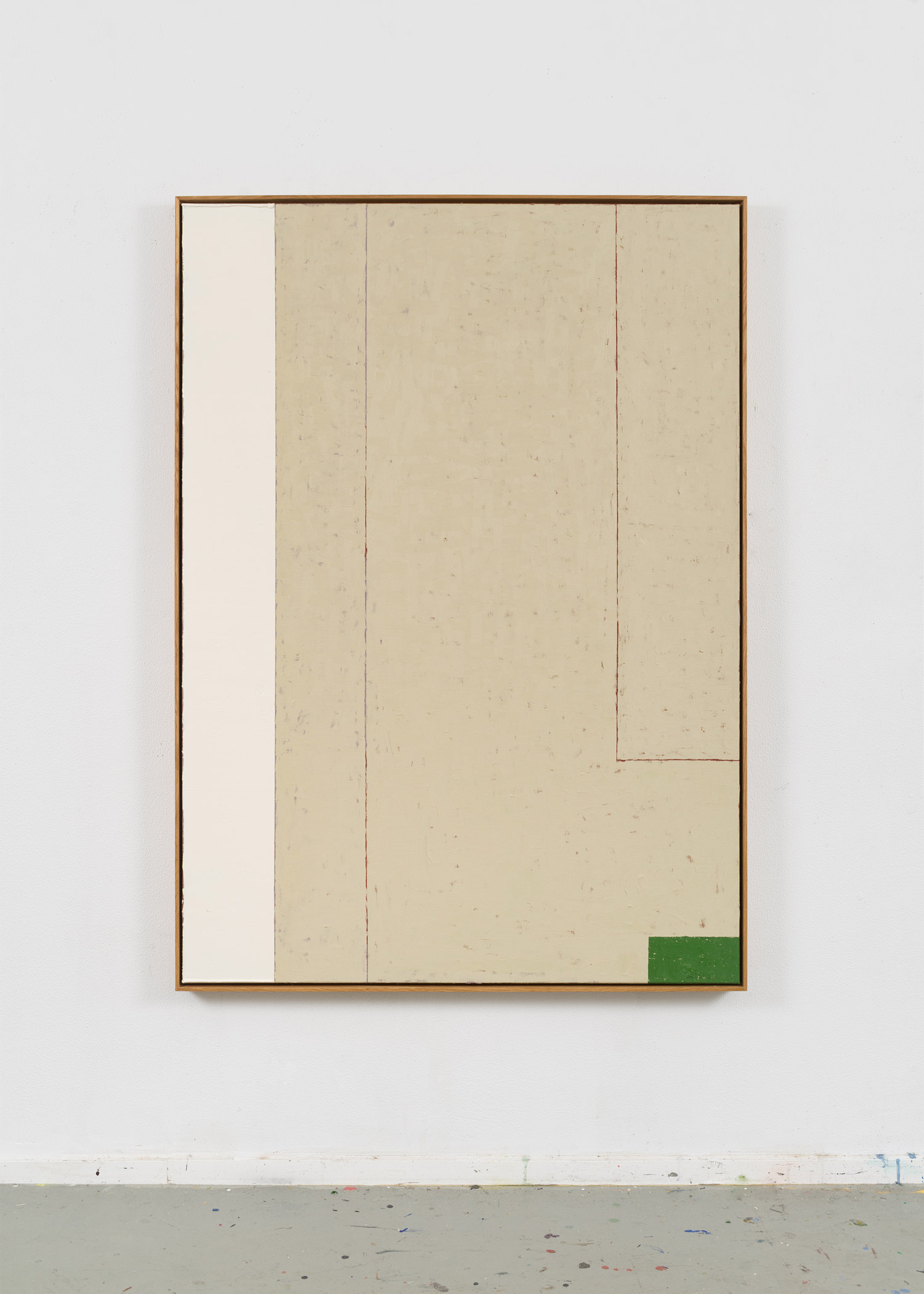

It’s hard to put my work into words, and I’d rather show a picture. Imagine trying to describe the taste of a strawberry – everyone experiences it differently. I operate in a tension between the very concrete and the very expressive. On one hand there are hard-edged grids, measured rectangles and quiet surfaces; on the other, there are gestural marks, scratches, and splashes.

I think of the painting as a puzzle where I don’t know the pieces yet: I pull down shapes, colors, and lines and try to fit them into a composition that feels right. Mood and rhythm matter more than representation. Form, color, and plane are my tools; an odd color or unpainted passage is often left as a “way out” so the work doesn’t become too perfect. The result should be like music – stretched tight, with just enough notes to make it resonate.

Please tell us more about your creative process. How do you go from the idea to the finished artwork? Is it an intuitive exploration or rather a conceptual approach while working?

My process always moves between instinct and control. Most paintings begin with an impulsive act: throwing paint, drawing with an oilstick, pouring gel. Then a more deliberate phase sets in. I tape off areas, layer matte and glossy mediums, sand surfaces and revisit them until they cohere. There’s no fixed plan – I might have an idea of where a work should go, but it always shifts as the material pushes back.

Some days the painting and I are best friends; other times we’re at war. I often think I can solve a problem with three more moves, only to discover I’ve painted myself into a corner. That frustration is part of it. If every idea worked the first time, the painting would be boring.

Some days the painting and I are best friends; other times we’re at war.

Which part of your creative process do you enjoy the most, and why?

What I love most is the moment of immersion – when time disappears and I’m fully inside the painting. It’s the same sensation I felt as a teenager at those evening classes: arriving at the studio, starting to work and suddenly realising hours have gone by. I also enjoy the puzzle-solving aspect, that dance between chaos and order. Finding the exact point where the composition snaps into place is deeply satisfying. At that moment the painting stops being a set of marks and becomes its own entity with a distinct mood.

Your works often invite a slower way of looking – layers, textures, and subtle shifts emerge only over time. How do you see the role of time and patience, both in the making and in the experience of your art?

Patience is a paradox in my work. Personally, I’m impatient; I’d love everything to resolve quickly, but paintings often resist. They require detours, sanding, reworking, and waiting. There’s the literal time it takes to make a painting and there’s the time it asks of the viewer. Photographs flatten the work, but standing in front of the surface, you see layers of brushwork and subtle shifts in texture. Even large areas are painted with a small brush, leaving the surface open so the “undercarriage” shows through. The burnt wood reliefs intensify this; the cracked black surfaces change with the light and invite reflection. I want the work to hold over time, not just in the weeks after it leaves the studio. Imperfections and material oddities keep it alive; they make the painting something you can return to and discover new things.

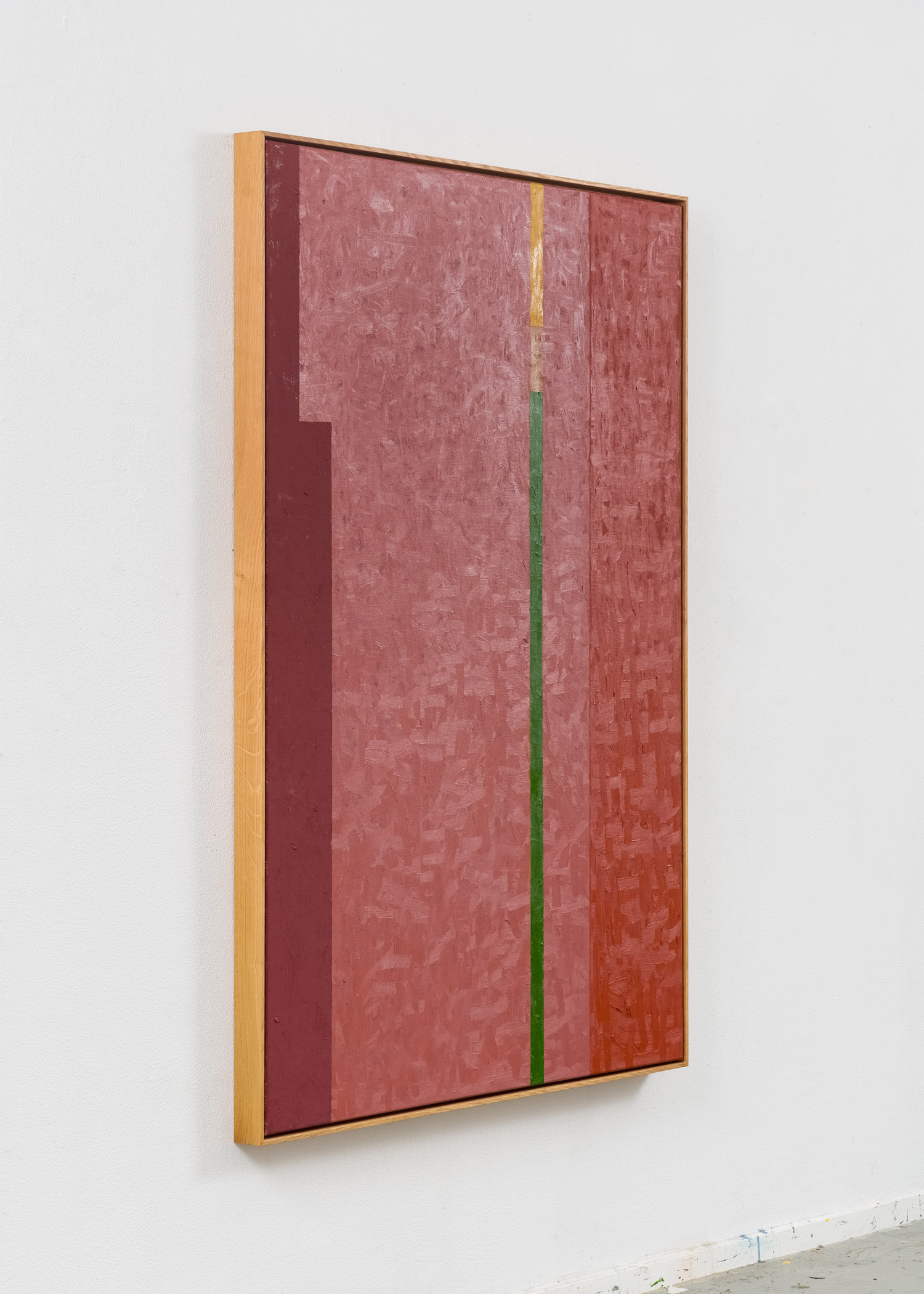

Your latest colorful works appear surprisingly emotional, despite their geometrical austerity. What, in your opinion, constitutes the power of color, and what led you to return to it after such a long dedication to black?

After five years immersed in monochrome black, I felt a need to challenge myself. The 2024 exhibition “I Call This Color” marked my return to a vivid palette. Working only with black had been intense and rewarding, but if I kept doing it forever, I’d be bored. Color introduces vulnerability and risk. It complicates compositions, makes relationships between areas unpredictable, and heightens the emotional temperature.

In recent works I’ve let metal paint rub against oil, allowed bright hues to clash, and reintroduced splashes and drips from earlier periods. People have called these paintings more “emotional,” but I don’t set out to illustrate feelings. I think in terms of atmospheres – warm versus cold, high-key versus muted – and try to calibrate a mood across an exhibition. Color painting is exhausting in its own way, so I may return to monochrome to focus on light again, but the oscillation keeps me curious.

What I love most is the moment of immersion – when time disappears and I’m fully inside the painting.

And finally: What are you currently working on, and what are your plans for the future? Are there any topics you would like to explore further?

I’ve just finished several projects – a group of blue monochrome works – with one or two red pieces – for a gallery in Paris and a solo show at Lundgren Gallery in Mallorca. The space is generous, so I’ve made fourteen big paintings with bold colors, unexpected clashes, metal paints, and splashes. I’ve revisited techniques I abandoned fifteen years ago and used them in new contexts. After this, I expect something from my current shows will carry into the next series; there’s always a thread. I suspect I’ll return to a more monochromatic palette for a while – color is demanding, and I’m curious to explore light again. What remains constant is my desire to keep my “ladder clean”: to stay true to my core interests while welcoming surprises.