In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with Line Nilsen.

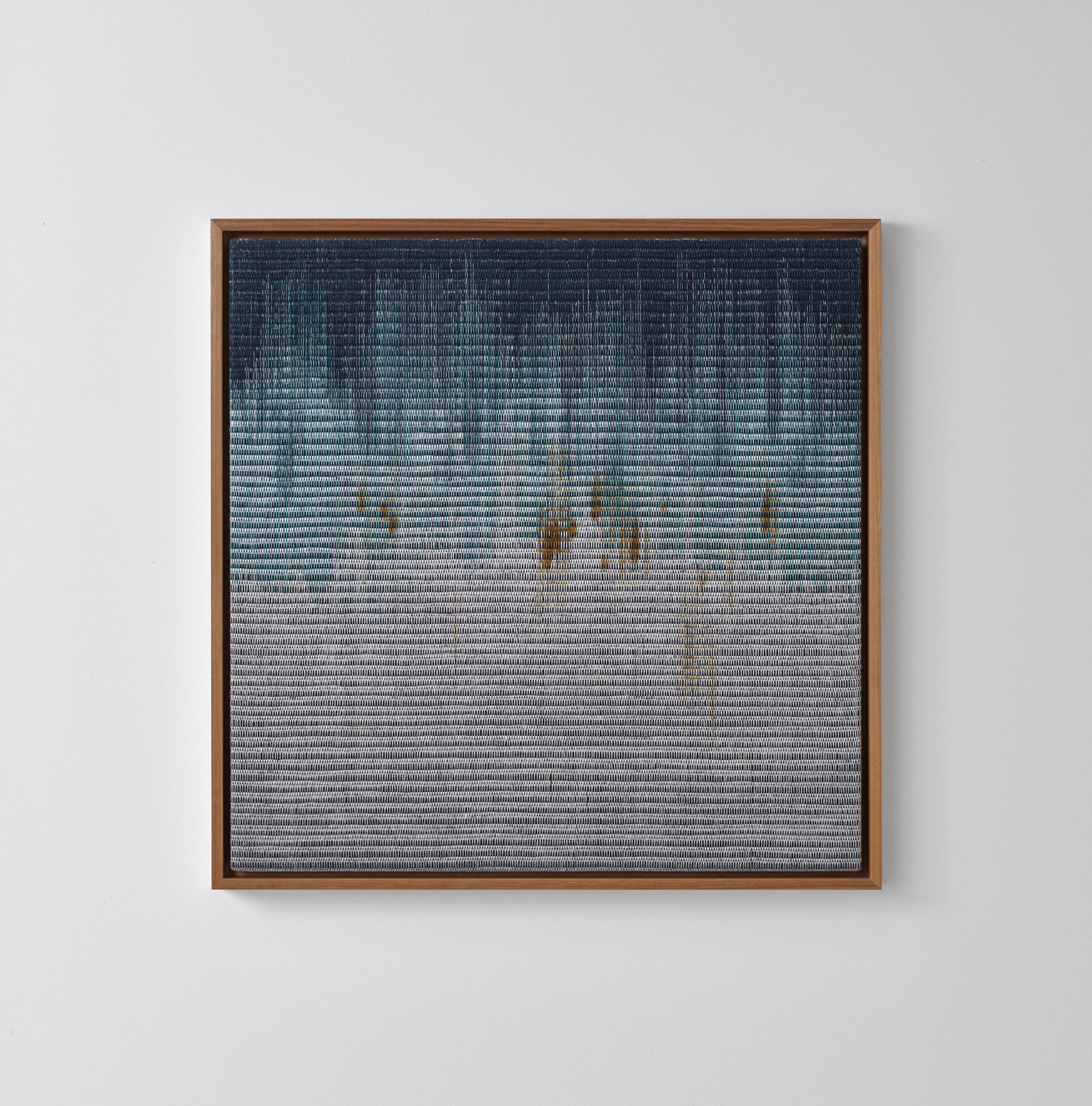

Line Nilsen (b. 1985) is a Norwegian artist, designer, and hand weaver based in the UK. Deeply rooted in craft and process, her work explores the interplay of material, color, and light. Drawing inspiration from the vast landscapes of Arctic Norway she grew up in, Nilsen’s minimalist compositions distill her memories into meditative woven artworks. By hand-dyeing and painting sections of her warp threads by hand, she creates delicate gradients and tactile surfaces that blur the boundaries between painting and textile art.

In this interview, I spoke with Line about how her childhood in the Arctic landscape continues to influence her creative vision, her fascination with old weaving techniques, and her approach to color and materiality. We also discussed the mindful, meditative qualities of traditional craft in a digital age and what it means to create work that is both contemporary and deeply connected to tradition.

Line, thank you so much for your time! Please tell us, how did you get into art? What led you to weaving, and how has your relationship with the medium evolved?

My journey into art began in childhood, though I wouldn’t have called it “art” back then. I grew up in a small town in Northern Norway, surrounded by mountains, water, and long seasonal shifts in light and dark. Creativity was simply part of how I experienced the world. I was fortunate to grow up in a creative family that always encouraged me to make things – there was no pressure to choose one path, only freedom to explore.

As a child, I filled my days with song, dance, imaginary play, drawing, sewing, knitting, collage – anything that allowed me to create. I was always surrounded by fabric and yarn. Looking back, those small moments built a strong foundation: they gave me confidence in materials and a love of working with my hands.

Initially I thought my future would be in fashion. I trained in men’s tailoring, which gave me a deep respect for craftsmanship, form, and precision. But I quickly realized that fabric itself was what fascinated me most – the structure, the feel, the way it behaves. That led me to study textiles, where I was introduced to both print and weave in my first year. The first time I sat at a loom, I felt something click. The structure, rhythm, and tactility of weaving spoke directly to me, almost as if I had found a language I didn’t know I was missing. Suddenly, learning felt effortless – I had found my place.

Over time, my direction shifted from fashion to interiors, and finally toward weaving as an artistic medium in its own right. Weaving became less about producing fabric and more about expressing ideas. When I began painting directly onto the warp, I realized the loom could be a canvas in itself, and my practice expanded into something more hybrid and expressive. Today, weaving is no longer just a technique for me – it’s a way of seeing and a language through which I can explore color, rhythm, and memory.

Weaving is no longer just a technique for me – it’s a way of seeing and a language through which I can explore color, rhythm, and memory.

Tell us more about your time in the Arctic landscape of Norway – how did that environment shape your artistic work? What memories or feelings of that landscape are particularly present when you weave?

Kirkenes, my hometown, sits at the end of a fjord surrounded by mountains and water. What makes it unique isn’t just the geography but the seasons. Winters are long, dark, and cold; summers are bright, euphoric, and full of endless light. That rhythm of extreme contrasts gets under your skin. As a child I didn’t question it – it was simply life. But as an adult, especially after leaving, I feel those seasons more intensely.

The winters can feel heavy, like a blanket: comforting in their stillness, but also demanding. The summers, by contrast, are full of energy. I remember staying awake through the night under the midnight sun, playing outside, swimming in lakes, feeling completely free. Those experiences of light, colour, and atmosphere live with me, and they come back through painting and weaving almost unconsciously.

My use of color – soft gradients, sudden contrasts, or muted tones – often reflects those memories. The repetition and processes of weaving feel connected to seasonal cycles too. Through my work, I try to share glimpses of that landscape, not literally but as an atmosphere or memory.

You are not only an artist but also a designer. How do these two disciplines influence each other in your creative work?

For me, the two are inseparable. My design background has shaped how I think about composition, color, and function, but it also keeps me precise and attentive to detail. I like things to be beautifully made, well-finished, and thoughtful in their execution. That sense of refinement definitely comes from design.

At the same time, weaving isn’t just design – it’s also a deeply emotional and expressive act. When I paint onto the warp, that’s where intuition takes over. I allow myself more freedom and play, letting the brushstrokes carry feeling rather than control. I think of it as a balance: the designer in me creates structure and discipline, and the artist in me introduces spontaneity, risk, and emotion. My work wouldn’t exist without both.

You combine painting and weaving in your art. What attracts you to this intersection, and how do you define the boundaries between the two disciplines?

I’ve always been drawn to the tension between control and freedom, and painting on the warp allows me to bring both into my work. Weaving is highly structured: you follow precise steps, and once the loom is set up, the process is slow and deliberate. Painting, by contrast, is immediate, expressive, and open to chance.

The first time I painted directly on the warp was at university, but I only rediscovered it years later while preparing for an exhibition. I hadn’t painted in years, and suddenly the act reignited something in me. I fell in love again with how color fragments, disappears, and re-emerges once woven. It felt like discovering a new language hidden inside the loom. Since then, it’s become an integral part of my process.

That stage carries a lot of pressure. By the time I’m painting, I’ve already invested days or weeks in preparing – so each brushstroke matters. But I thrive on that risk. It forces me to be present, to slow down, and to make intentional decisions.

For me, the boundaries between painting and weaving blur completely. Sometimes I describe what I do as re-engineering a canvas: I paint before the “canvas” even exists, and then I weave it into being.

Sometimes I describe what I do as re-engineering a canvas: I paint before the “canvas” even exists, and then I weave it into being.

Tell us a bit about your creative process – how do you prepare and plan a new work, and what role does your intuition play in this process?

My process is quite organic. Each work tends to grow out of the last, almost like a conversation. While I’m weaving one piece, I’m already imagining the next – wondering what would happen if I used finer yarn, introduced a different paper, or shifted a color slightly. Accidents often lead to new directions too: a brushstroke gone astray might spark a whole new series.

Much of my planning happens in my head. I think through the process obsessively before starting so that when I finally sit at the loom, it feels natural. I do make sketches or watercolors sometimes, especially for commissions, to give a sense of direction. But intuition is always central. I need space for spontaneity; otherwise, the work feels too rigid.

Your works are very reduced and minimalist. However, many artists reject the term “minimalist” as a description of their own works. How do you feel about the term?

I don’t mind it at all – I am, after all, Scandinavian! Minimalism feels very natural to me, both culturally and personally. I love minimal art; it brings me calm and clarity in an otherwise chaotic world.

That said, my work isn’t about stripping things away for the sake of it. It’s about distilling experiences into their essence – reducing color, form, or rhythm until what’s left feels true.

What is ironic is that my personality is far from minimalist, but that is a whole other story…

My work isn’t about stripping things away for the sake of it. It’s about distilling experiences into their essence – reducing color, form, or rhythm until what’s left feels true.

Your works radiate a calm, quiet atmosphere. What do you hope your works will evoke in the viewer?

I hope they evoke a sense of place, even if it’s not a literal one. Maybe it reminds someone of a landscape they know, or maybe it sparks a memory or emotion that feels familiar but hard to name. I think of weaving as a way to create atmospheres – quiet spaces where the viewer can pause and feel something personal.

Living in the UK, I’m often struck by the differences between here and Norway. At times I feel like a stranger to the landscape, but weaving helps me bridge that gap. When people connect with my work, often we end up talking about their own places, memories, and experiences. That exchange feels deeply rewarding – it creates connections through craft, process, and shared human experience.

What are you currently working on, and what are your plans for the future? Are there any new themes or techniques you are excited to explore further?

I’ve recently installed a wider loom, which opens the possibility of making very large-scale works. I’m excited by the physicality of weaving on this scale – it feels immersive, both for me as a maker and for those experiencing the finished piece.

My newest body of work explores themes of nature, foraging, and heritage. Since becoming a parent, these themes have become more meaningful. I think a lot about how we pass on traditions, knowledge, and our relationship with nature to the next generation. These works are a way of exploring those questions visually, in an abstract, woven language. My hope is that they will grow into a solo exhibition.

Alongside this, I’m working on a few commercial commissions and creating new pieces for galleries and art consultancies. Moving between different scales and contexts feels refreshing – it reminds me that weaving, in all its forms, always holds new possibilities.

Thank you so much, Line!