The assumption that a minimalist and abstract aesthetic is a style of the modern era seems plausible at first glance. But what inspired artists of that time to reduce their works so drastically to the essentials? Surprisingly, we find the answer in a millennia-old culture that already possessed an aesthetic that seems astonishingly modern to us today, as artists such as Constantin Brâncuși, Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, Barbara Hepworth, and Amedeo Modigliani used artifacts from the early Cycladic culture as inspiration for their work.

So the question arises: How could archaic finds from such an ancient era influence the artists of modernity so profoundly in their creations?

When I speak of Cycladic culture, I am referring specifically to sculptures created about five thousand years ago in various regions in Greece. The Cyclades are a group of islands in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The various natural resources, including gold, silver, copper, obsidian, and marble, found on many of the islands have contributed to the tremendous prosperity of the inhabitants and their culture. Most of the artifacts are from the so-called Early Cycladic period, which ranges from 3200-2000 BCE. Scholars divide this period into three phases: EC I, EC II, and EC III.

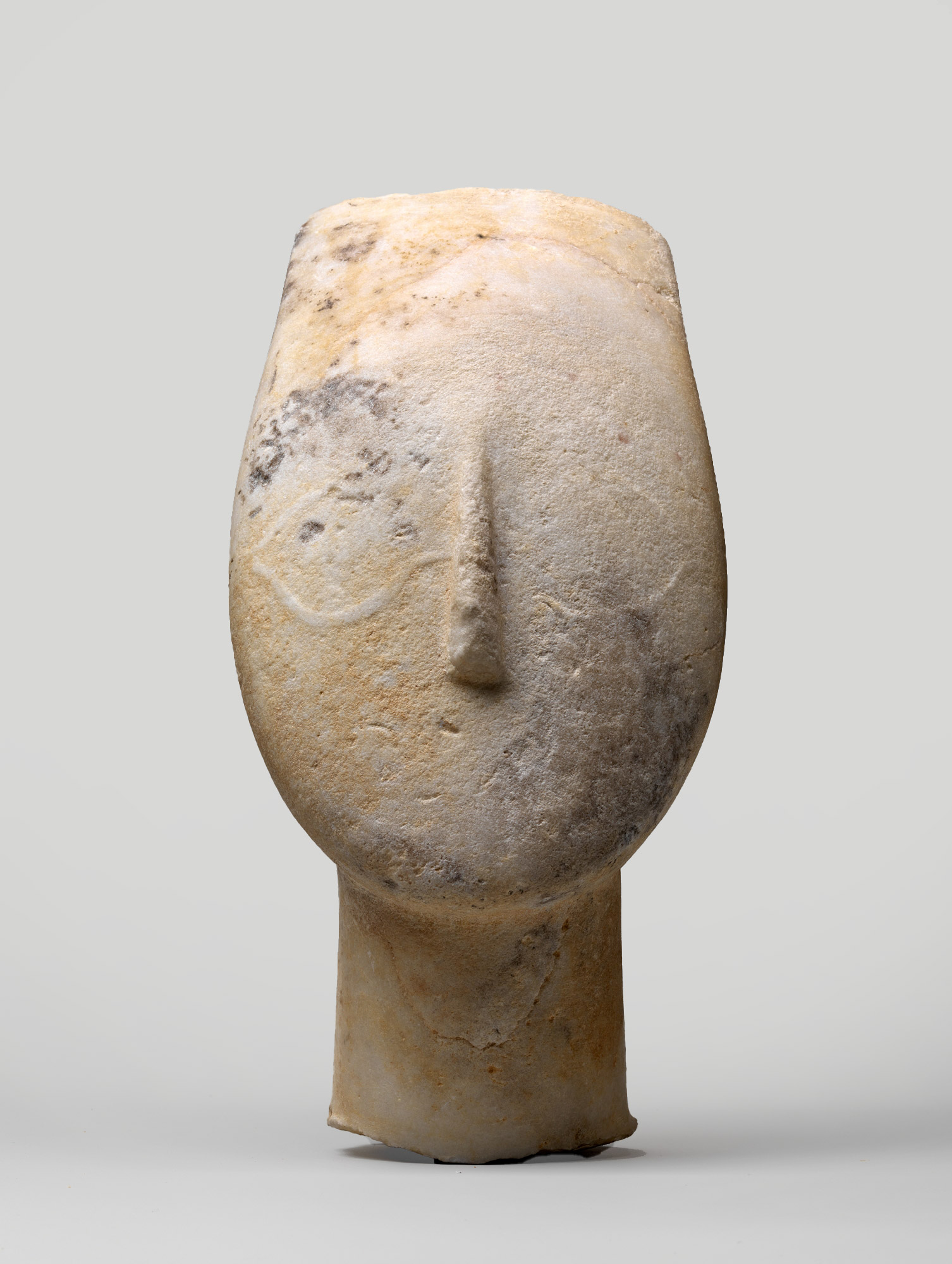

The artifacts, also called “idols” from the Greek word “eidolon”, were often found in graves and cemeteries – but their exact function remains unclear to this day. Most of the sculptures were made of white marble. It was carved with stone tools: First, the marble was roughly shaped with a hammer, and then the surface was smoothed and polished with an abrasive. This process was time-consuming and required a high degree of skill.1 Their size varies greatly from small and handy to life-size. The feet were often pointed, indicating a horizontal position.

Remains of paint pigments were found on some of the sculptures, especially in the facial parts. This suggests that they were originally painted. The figures are striking for their pure and abstract design and the harmony of their proportions. The sculptors of that time apparently followed strict aesthetic principles regarding form and beauty.2 This becomes very clear in Pat Getz-Preziosi’s book, in which she shares her detailed observations.

At the beginning of the 19th century, travelers found these marble figures and brought them to Europe. They were exhibited in local museums – but the response was not very positive. They were considered “ugly” and “primitive”, as Pat Getz-Preziosi describes.

It was not until the early 20th century that artists such as Constantin Brâncuși, for example, recognized the hidden beauty of these sculptures. It was a time of awakening. Avant-garde artists were searching for a new form of art, beyond traditional representation. They wanted to capture the essence, to make the universal visible. The smooth, white surfaces of the marble, the abstract and reduced formal language and the calm power of the sculptures captured the attention and interest of these artists and were exactly the inspiration they were looking for.3

Marble head from the figure of a woman, Early Cycladic II, 2700–2500 BCE, Marble, 25.3 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA available under Met’s Open Access policy (CC0)

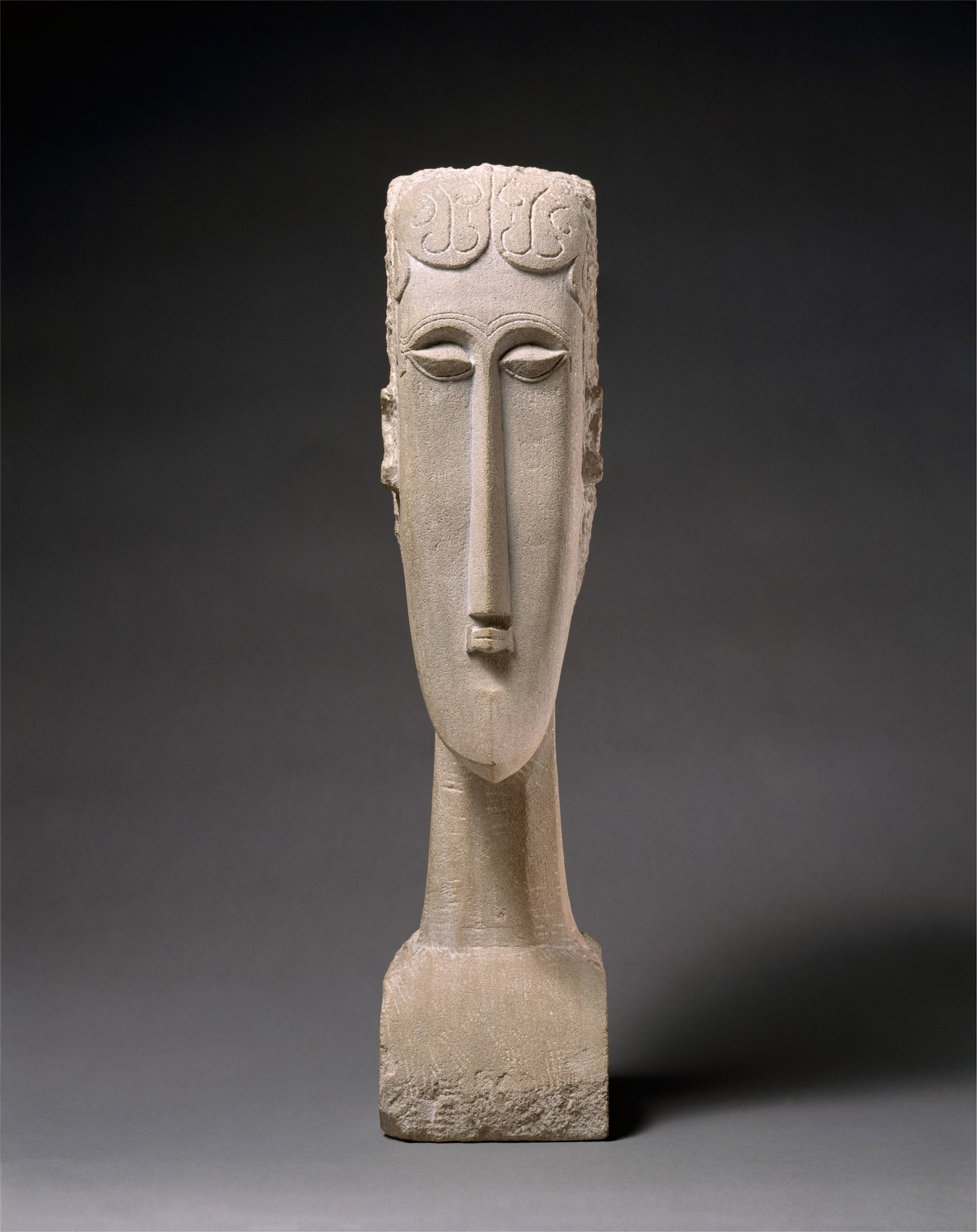

In Brâncuși’s sculpture “Muse” from 1912 this influence is visible: in this work, Brâncuși reduces the characteristics of the face to an abstract, almost geometric form, which resembles the reduction and abstraction of the Cycladic statues. Through this simplification, he managed to achieve universal beauty and harmony, which is also expressed in Cycladic Art.

Most of the sculptures from the early Cycladic period represent women in various forms; some have natural body proportions, while others are depicted in highly schematic shapes. Their forms were simplified to broad, flat planes, probably designed with a compass, protractor, and ruler.4

For Amedeo Modigliani, an Italian painter and sculptor who lived and worked in Paris in the early 20th century, the depiction of women was also a central theme in his work. He was fascinated by African art and was inspired by the formal language of the Fang masks of Gabon, among others. Nevertheless, the reduction and simplicity of Cycladic sculpture can also be found in his work. His sculpture “Woman’s Head” from 1912 (fig. 7) is a perfect example of how he took the Cycladic presentation of femininity and developed it in his own style.

The Ukrainian sculptor Alexander Archipenko, one of the pioneers of modern sculpture, always searched for the symbolically simplified form in his work. Contrary to popular belief, Archipenko did not draw his inspiration primarily from Cubism. He explicitly emphasized that his work was rather influenced “by the millennia-old artistic tradition of geometric reduction”.5 Pre-classical Cycladic sculpture in particular played an important role for him. His favorite motif was the torso, whose abstract, symmetrical formal language he liked to merge with modern design techniques, for example in one of his known works, “Torse plat” from 1914.

Barbara Hepworth, a British artist known for her abstract sculptures, also picked up on the aesthetic simplicity of Cycladic sculptures in her work: An influence reinforced by a trip to the Greek islands in 1954. She owned a small collection of ancient sculptures, including Cycladic idols. They served as a source of inspiration for her minimalist works, which are based on similar principles of abstraction and simplification.6,7

In his effort to capture the truth of essence in his art, Alberto Giacometti was also fascinated by this simplification. This was expressed in his conception of sculpture to be flat and little modulated, similar to the stylized forms of Cycladic Art, rather than aiming for realistic representation as practiced by artists such as Rodin or Houdon.8 (Here is a drawing by Giacometti from 1923, in which he explores the proportions of Cycladic sculptures). In his sculpture “Woman [Flat III]” from 1927, this view becomes particularly clear.

Looking at Cycladic Art today, we encounter an aesthetic that seems surprisingly modern despite its distance in time. It is fascinating how this millennia-old culture already developed a formal language whose essence lies in its reduced and abstract aesthetics. Herein lies a universal appeal: the representation of the human body in its most elemental form remains independent of time and culture.

Even though Cycladic sculptures were considered “ugly” and “primitive” at the beginning of the 20th century, they underwent a transformation through the influence of Brâncuși, Arp and co.: they became objects of admiration, symbols of human values and common origins.9 However, this also had its downside: many Cycladic artifacts were stolen from tombs to satisfy the increasing demand of collectors. Unfortunately, so many fake artifacts were put into circulation. This hinders current research and the preservation of Cycladic culture.

Today, these artists’ engagement with early Cycladic Art not only offers us a more profound understanding of universal forms and representations but also reveals the constant dialogue between past and present. A dialogue that shows us that the search for essence in art is a dynamic and ongoing journey in which the old constantly shapes and inspires the new.

So, is Cycladic Art the origin of minimalist aesthetics? Well, this question is certainly not so easy to answer because many cultures, regardless of time and place, used abstraction to express themselves. But we can be sure that the timeless formal language of Cycladic Art has certainly had a decisive influence on the reduced aesthetics of modern art.

Further Reading / Resources

- https://www.christies.com/features/Cycladic-art-a-guide-for-new-collectors-9983-1.aspx

- Page 87 – Pat Getz-Preziosi, Early Cycladic Sculpture – An Introduction, The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California, 1985

- Pat Getz-Preziosi, Early Cycladic Sculpture – An Introduction, The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California, 1985

- Page 57 ff. Pat Getz-Preziosi, Early Cycladic Sculpture – An Introduction, The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California, 1985, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ecyc/hd_ecyc.htm

- https://www.staatsgalerie.de/g/sammlung/sammlung-digital/einzelansicht/sgs/werk/einzelansicht/1282F5DD4871F34C8BD0378F5EA972B4.html

- https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/impressionist-modern-art-day-sale-n09861/lot.311.html

- https://hepworthwakefield.org/

- https://www.jimcarrollsblog.com/blog/2019/9/11/not-just-reality-but-truth-giacometti-and-the-virtues-of-style

- https://cycladic.gr/en/page/i-morfes-tis-archis

- “Risk and Repair in Early Cycladic Sculpture”: Metropolitan Museum Journal, v. 16 (1981)

- https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/demystifying-cycladic-figurines/

- https://kallosgallery.com/blog/31-simplicity-is-complexity-resolved-constantin-brancusi-cycladic-stone-through-a-modern-lens/

- https://cycladic.gr/en

- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ecyc/hd_ecyc.htm