In modern and contemporary art, there are few styles as controversial as monochrome painting. An artwork with only one color seems too one-dimensional and empty to many at first glance, but actually, this is one of the most fascinating forms of art. By limiting the visual palette to one color, a monochrome painting forces the viewer to look beyond this limitation and explore the ideas, and concepts that the artwork conveys. In this week’s essay, we delve into the world of the monochrome. We’ll illuminate what makes it special and how it can shape the appreciation of art.

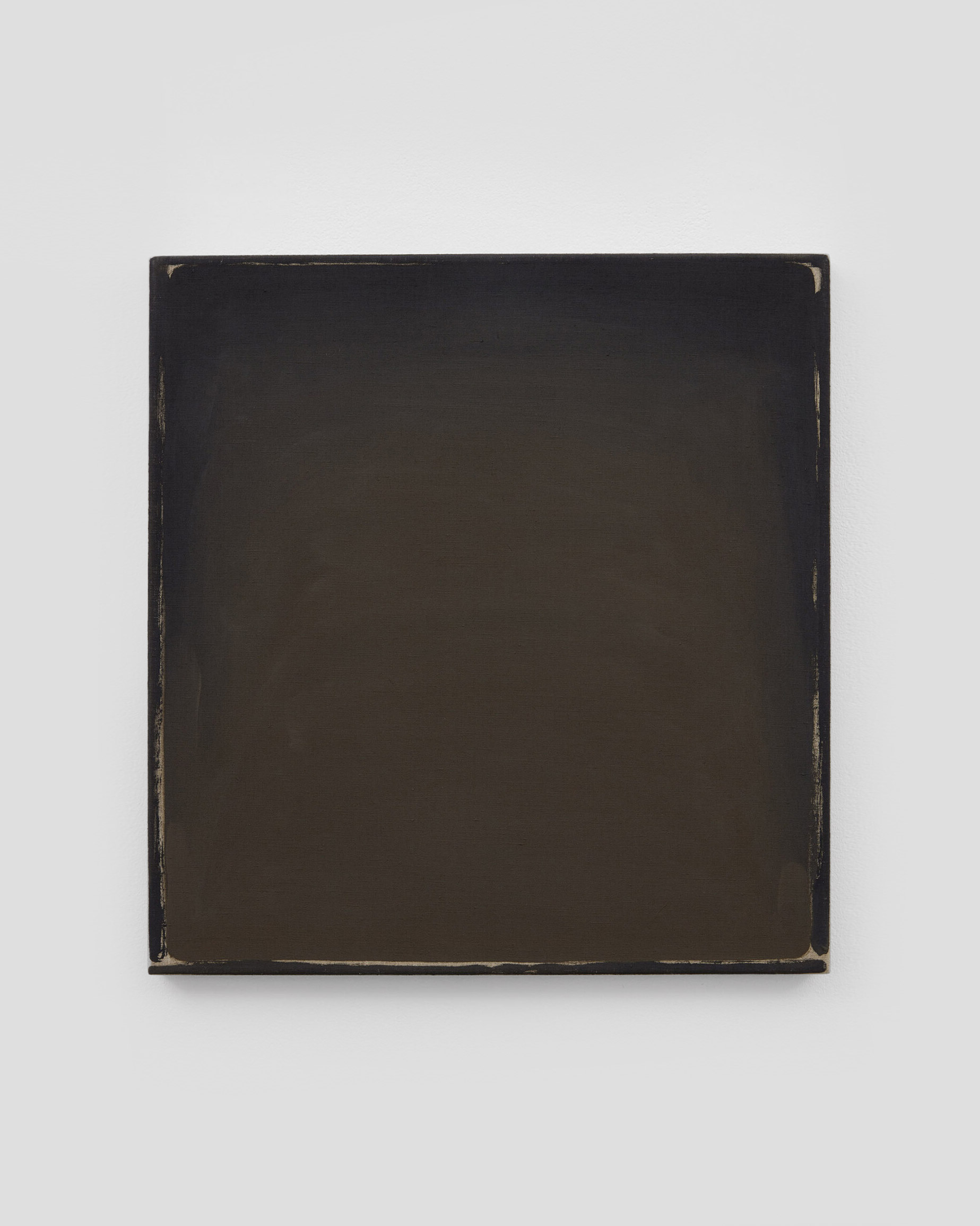

One of the main characteristics of monochrome painting is its reduction to a single color or shades of the same color. The first documented monochrome dates back to 1617. The English Paracelsian physician Robert Fludd published an all-black painting titled “Darkness” about the origin and structure of the cosmos. The painting was meant to represent the nothingness that preceded the universe.

The Monochrome as a new beginning

It wasn’t until over 200 years later that more artists began experimenting with monochrome paintings, including Paul Bilhaud (1882) and Kazimir Malevich (1915). Pablo Picasso also made many paintings in shades of blue between 1901 and 1905, which is known as his “Blue Period.”

After 1945, the non-objective monochrome stood as a symbol of a new beginning. It was a reaction to the cultural rupture of World War II. The reduction to a single color led to a radical shift away from the depiction of objects toward pure form. This caused a defensive reaction among many viewers, ranging from incomprehension to aggression.

Artists such as Yves Klein and Barnett Newman saw their paintings become the subject of laughter, ridicule, and even vandalism in exhibitions. If art offered comfort and distraction to many people at that time, they felt let down by monochrome paintings and challenged in their understanding of art.

Fortunately, such reactions did not stop artists from continuing to experiment with just one color. Ad Reinhardt, for example, began to work more intensively with the color black around 1953. The fascinating thing about his work is that the perception of his large-format paintings changes the closer you get to them – you recognize subtle shades of red, green, and blue. He explored the limits of vision, perception, and thought in his paintings. He asked questions about the nature of vision, the potential of color, and the relationship between art and reality. Agnes Martin, on the other hand, explored silence in her bright, monochrome and minimalist paintings (such as “Untitled” from 1959). Her work was influenced by Zen Buddhism and the Chinese Tao philosophy, in which the color white was associated with various spiritual meanings such as purity, emptiness, or nothingness.

Artists such as Mark Rothko, Robert Ryman, Olivier Mosset, Brice Marden, and Pierre Soulages are also among the outstanding representatives of this art form, each of whom developed their own unique interpretation of the monochrome.

Monochrome painting in Korea

At the same time, interest in monochrome paintings also blossomed in Korea. Dansaekhwa is what we call this movement today. Dansaekhwa, translated as “monochrome painting” is a Korean art movement that developed in the 1960s and 1970s. It emerged in the midst of social and political upheaval in postwar Korea when the country was liberated from Japanese colonial rule. This turbulent period led to a search for a new artistic identity that was distinct from Western and traditional Korean influences.

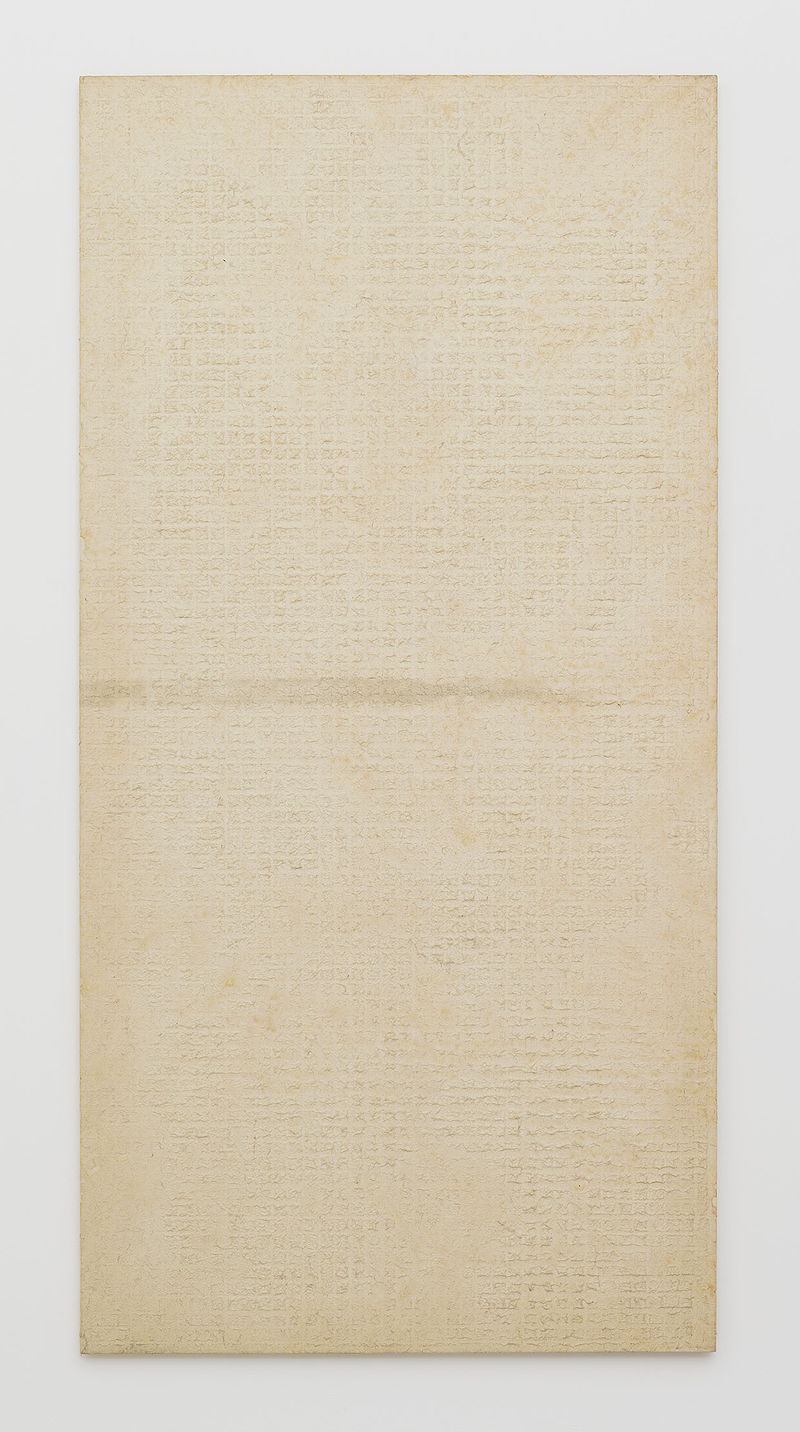

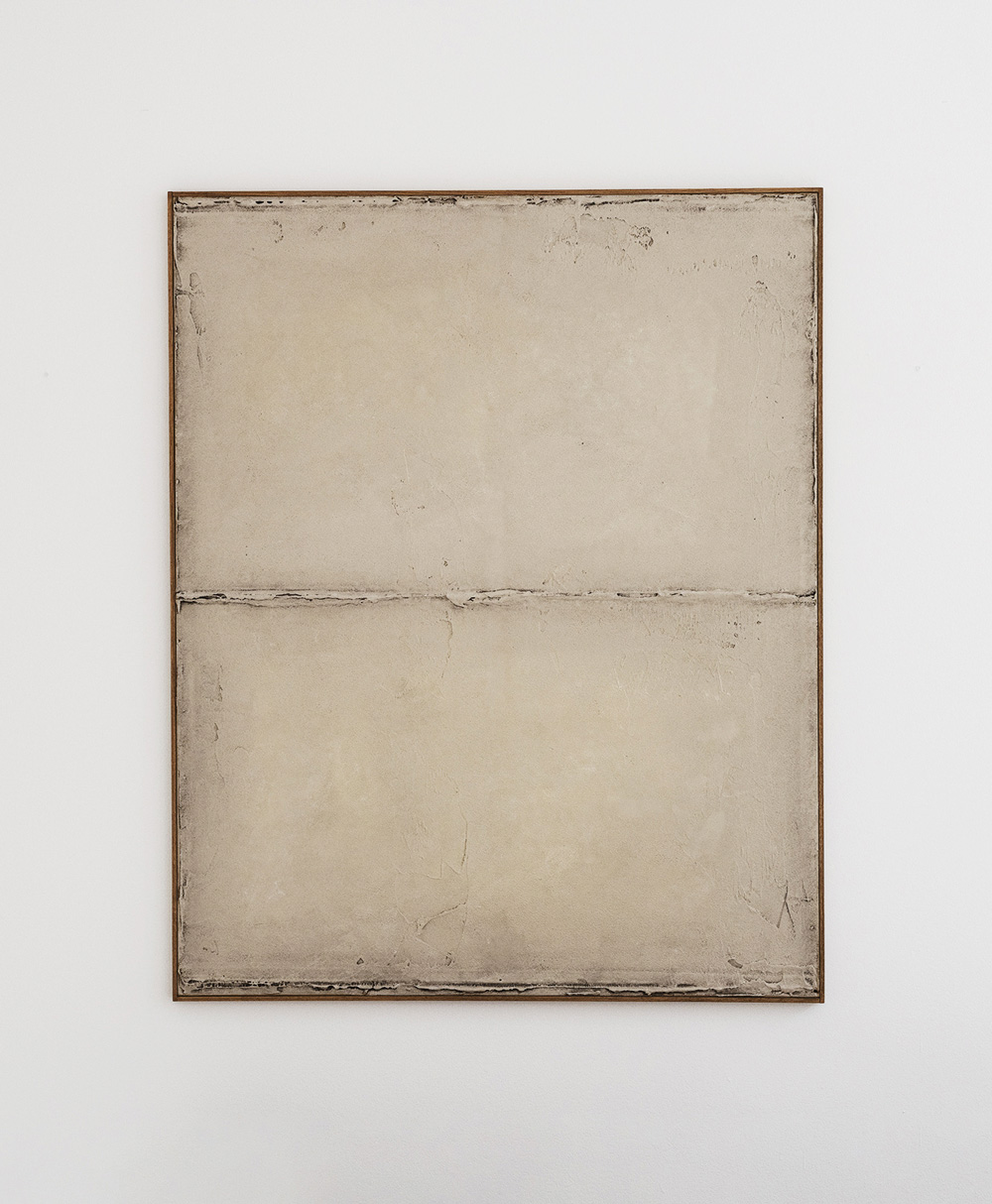

Representatives such as Park Seo-Bo, Chung Chang-Sup (see fig. 1 and 2) used repetitive, rhythm-like gestures in their paintings. In this way, they explore the relationship between the materials used and the artist. Park Seo-Bo once said about the movement: “In fact, Dansaekhwa’s art is not so much about the color as it is about the essence of the action itself – the repetitive gestures that empty and cultivate the painter’s mind.”

It is fascinating that in times of upheaval and unrest, artists completely independently used the reduction to one color. Through the absence of narrative elements, the monochromes invite the viewer to a meditative contemplation and a deeper understanding of their own existence and the world around them. The painting thus becomes a sanctuary of peace and tranquility.

Hidden complexity: The monochrome as a viewing experience

Monochromes are certainly an art form that offers a lot of room for interpretation. Artists used it to spiritually explore a new level of perception of art. The strength of monochrome painting lies in its ability to take the viewer on a journey into the innermost part of their perception. By reducing the work to one spectrum of colors, the focus is directed to the relationship between light, shadow, and texture. This creates an intense experience of color that is enhanced by the absence of other elements. This teaches us that it is not always complexity that makes the extraordinary, but the ability to recognize and appreciate the beauty of the simple.

For me personally, looking at monochrome art is always a special experience. Because the more you approach the painting, the more details reveal themselves to the viewer – What emotions do I feel? What changes in my perception? How does the light affect the painting, how does it change the surface? This aspect of monochrome art is fascinating; the experience grows as I look at the painting and continues to unfold. This allows me to focus on the essence of the artwork. I become a part of the work and am not just a passive observer.

Further Reading / Resources

Title image made with Midjourney by Aesence